When Hippocrates said, “Let food be thy medicine, and let medicine be thy food”, he probably wasn’t thinking about all the dietary challenges that people with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) may face. Whether it’s having a long list of trigger foods or not pulling enough nutrients from the foods they can eat, getting proper nutrition can be a challenge for anyone struggling with their gut health. Vitamin and mineral deficiencies are a serious issue for many IBD warriors because of disease activity, medication, or surgeries that lead to the removal of sections of the intestine, as these factors can all affect the body’s ability to absorb and process nutrients.

With so many factors at play, nutrient deficiencies can be a complicated topic to digest. Remember that although this information does not replace medical advice, it can be used to help you advocate for yourself! Knowledge is power, so let this information be a tool to help you and your medical team find a health plan that is tailored to your needs and patient journey.

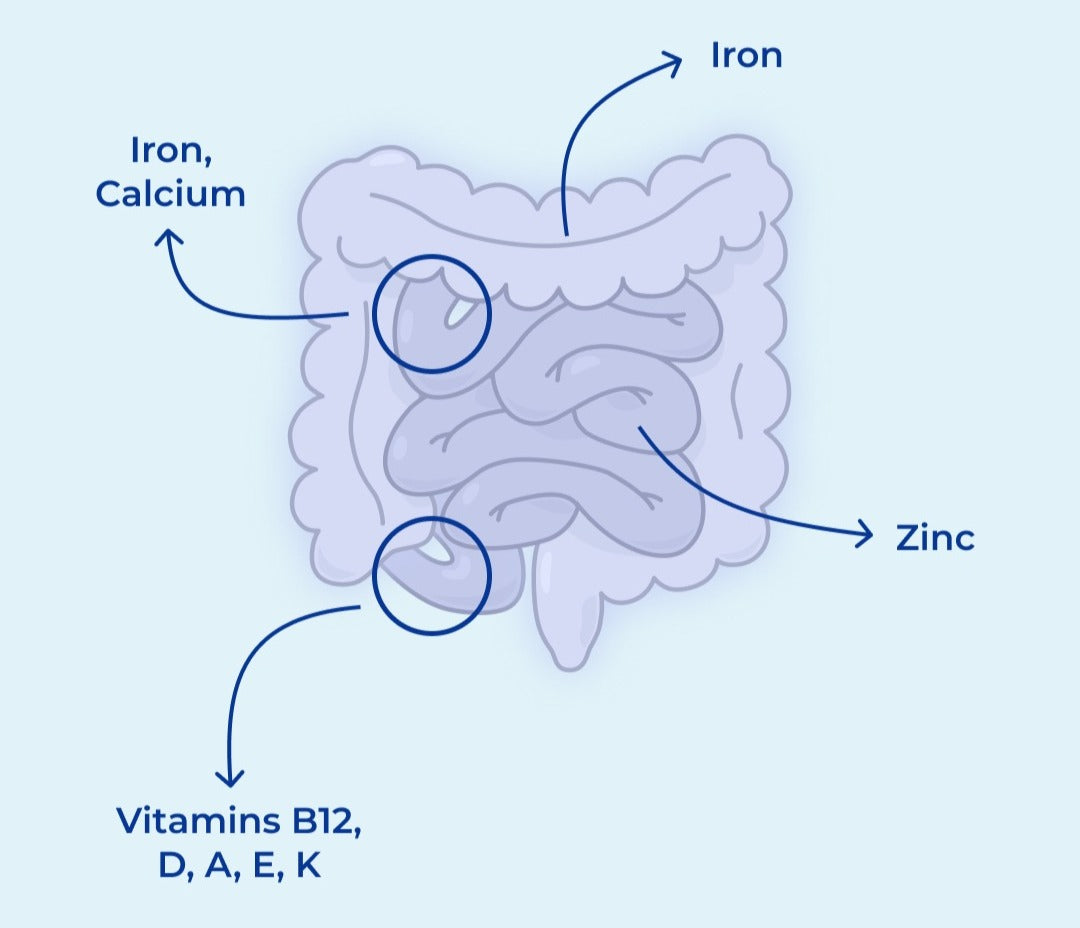

If you have IBD, there’s a lot to think about. It’s important to look out for nutrient deficiencies like iron, vitamins D, B12, A, E, K, calcium, folate, and zinc, because they are some of the more common vitamin and mineral deficiencies among patients with Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and all other types of IBD (1).

In our last post, we discussed the implications of iron deficiency for people with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). While iron deficiency is a common and risky issue for IBD patients, there are several other micronutrients that factor into IBD health. They’re all essential, but it may not be apparent why they’re so important, and why people with IBD have to pay special attention to make sure they’re getting enough of these vitamins and minerals.

So why might having low levels of one or multiple of these micronutrients be a concern? Why doesn’t everyone with IBD have the same deficiencies? How are these issues treated? If you have these types of questions, you’re in the right place.

Calcium

We’ve probably all been told to drink our milk to get calcium for good bones and teeth, but it’s not that simple, especially for people with IBD--and not only because many will avoid dairy products because of concerns that they will trigger digestive symptoms. These individuals tend to have low levels of calcium, leading to low bone mineral density. Calcium is an important part of intestinal, bone, and renal health, and is also used to facilitate muscle movement and communication networks between nerves throughout the body, among many other roles (2). Those on corticosteroid medications, with low bone density (osteopenia), or with osteoporosis in particular should be looking after their calcium levels. Plus, up to 70% of women with IBD could be missing enough daily calcium.

Much like iron, the body has a difficult time absorbing calcium in an active disease state. This is because the beginning portion of the intestine, known as the duodenum, will have a hard time taking up calcium if the area is inflamed (1,3).

Concerned about your calcium intake? Luckily for anyone in need of more calcium, plenty of foods supply it, including dark leafy greens, shrimp, sardines, salmon with bones, and tofu, not to mention milk products such as kefir and yogurt, along with foods that are fortified with calcium (4). It’s best taken with vitamin D, making vitamin D that much more important for those with calcium deficiency.

Vitamin D

If you read our article on the role of vitamin D in Crohn’s disease, you’ll know that vitamin D does a lot, notably regulating inflammation through the immune system. Healthy levels of vitamin D are also associated with reduced disease activity among those with IBD. People with reduced nutrient absorption, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), or who are on corticosteroids are particularly at risk of being deficient in vitamin D as well (5). This is because corticosteroids can induce vitamin D resistance, which inhibits vitamin D absorption and thus affects all the processes that rely on vitamin D processing (4). New research also suggests that vitamin D resistance contributes to the development of autoimmune disease (6).

Vitamin D is one of several fat-soluble vitamins, which simply means that it’s processed with fats from your diet and stored in the liver and fatty tissues (7). Fat-soluble vitamins may not be absorbed enough if disease activity is present in the last portion of the small intestine before the colon, known as the terminal ileum (4).

Looking for ways to increase your vitamin D levels? There’s supplements and sunshine, but also plenty of food options that contain the vitamin, especially fish like salmon, tuna, sardines, and cod liver oil, in addition to milk, orange juice, egg yolks, and fortified yogurt (4).

Vitamins A, E, K

Speaking of fat-soluble vitamins, vitamins A, E, and K are also part of this category. To put it simply, these fat-soluble vitamins do a lot. They’re involved in producing cells and protecting them from damage, creating blood, fighting infections, and promoting bone health. In people with IBD, inflammation of the bowel (particularly in the terminal ileum of the small intestine), short bowel syndrome (when people don’t have enough small intestine to absorb nutrients from food), or blockages from the intestinal tract to the liver can lead to fat malabsorption, meaning fats are not being properly processed in the body. This leads to low levels of vitamins A, E, and K.

Here’s some foods that contain these micronutrients (4):

- Vitamin A: carrots, red peppers, broccoli, mango, sweet potatoes, cantaloupe

- Vitamin E: almonds, sunflower oil and seeds, peanuts, wheat germ oil

- Vitamin K: dark leafy greens, cauliflower, soybeans, okra, cabbage, pomegranate juice

Vitamin B12

Vitamin B12 is yet another vitamin that is absorbed at the end of the ileum. It’s a crucial component of red blood cell production, making new DNA, and maintaining healthy nerve function. Getting enough vitamin B12 may be difficult for people whose Crohn’s disease affects the ileum, since it’s the only region in the entire body where this vitamin can be absorbed from food. Vitamin B12 deficiency can manifest as anemia, cognitive issues, irregular bowel habits, poor memory, heart disease, bone fractures, and more.

What makes vitamin B12 extra special is that we can’t make it ourselves, and neither can any of the foods we eat, like plants and animals. So how does vitamin B12 get into the food we eat? Our favorite friends, bacteria. Animals eat from the soil or other animals, both of which can contain diverse microorganisms that produce vitamin B12. In fact, a long list of bacteria are involved in creating vitamin B12 through a complicated process. People who follow a plant-based diet may also have trouble getting enough vitamin B12 from their diet, because the predominant sources of it are beef, liver, trout, tuna, clams, and milk (4). However, there’s no need to worry if you’re vegetarian or vegan. There’s plenty of foods fortified with vitamin B12, such as tempeh and nutritional yeast, but supplements are also available for those who are deficient regardless of their diet.

Zinc

Zinc is best known for its ability to boost the immune system to help fight against pathogens, which are microorganisms such as bacteria and viruses that can threaten your health. Symptoms of IBD like short bowel syndrome and severe disease activity can affect zinc levels. Severe inflammation across any part of the small intestine can affect how much zinc can be absorbed by the body to help the immune system function properly. Consequences of zinc deficiency could be poor wound healing, hair loss, diarrhea, and changes in the ability to taste and smell. Much like vitamin B12, vegetarians are often deficient in zinc. However, there’s plenty of options for things to eat to boost your zinc levels: legumes, nuts, bran, green peas, whole grains, and non-vegetarian options such as oysters, crab, shellfish, beef, pork, and poultry are some examples (4,5).

Folate (Folic Acid)

Folate deficiency is yet another reason why someone may become anemic, because it is involved in the process of creating new cells and maintaining their health. It also helps with the breakdown and use of fats and carbohydrates. IBD drugs such as methotrexate and sulfasalazine may interrupt folate absorption, and so can the removal of sections of the gastrointestinal tract, restrictive dieting, and SIBO, among other causes (5). Beyond anemia, folate deficiency could be linked to diarrhea, weight loss, mental instability, and memory loss (5). To make sure you have enough dietary sources of folate to avoid these risks, try incorporating one or many of these foods into your diet: rice, black-eyed peas, dark leafy greens, avocado, beef liver, kidney beans, or brussel sprouts.

Wrap-up

It may be frustrating to recognize how many micronutrient deficiencies are common for people with IBD, putting them at risk for further complications, but recognizing their importance, where the issues may originate, and how to circumvent these deficiencies can be invaluable. Having the tools and knowledge to listen to your body and discuss your nutrition further with a qualified health professional will help ensure that you get all the nutrients you need from diet or supplementation. Luckily, you can monitor your vitamin, mineral, and supplement intake at your fingertips by tracking your diet and medications with Injoy. This is a useful tool that you can utilize to your advantage to take control of your health. Download Injoy today!

Sources

- https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitamin-and-mineral-deficiencies-in-inflammatory-bowel-disease#:~:text=The%20most%20common%20deficiencies%20are,energy%20and%20protein%20in%20IBD

- http://uptodate.com/contents/regulation-of-calcium-and-phosphate-balance

- https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitamin-and-mineral-deficiencies-in-inflammatory-bowel-disease

- https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/diet-and-nutrition/supplementation

- https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/sites/default/files/legacy/science-and-professionals/nutrition-resource-/micronutrient-deficiency-fact.pdf

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.655739

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK218749/